This article explains the impact of stereotyping and expectations we have of our employees, as well as how engaging personas can be used as a framework to increase productivity in virtual teams.

Why do we stereotype? And how does stereotyping affect trust and performance in (virtual) teams?

A stereotype is a “fixed, over generalized belief about a particular group or class of people”. (Cardwell, 1996). Stereotypes help us simplify our social world and it enables us to respond rapidly to situations, but a disadvantage according to McLeod (2015) is that it makes us not see the differences between individuals.

Our brains cannot deal with missing information – we will add what we are missing, from what we already know. And if what we already know is negative about a certain group of people, and we attach that to a recently met colleague, the trust will suffer as “you can never give a second first impression” is valid for virtual environments as well. (Jarvenpaa and Leidner, 1998). Moreover, if what we already know about a group of people is not true about that particular person, productivity might suffer, as we will not be able to recognize the potential, and consequently motivate the team member to reach it.

Macrae and Bodenhausen (2001) discuss that at our encounter with a stranger, we tend to see the person as a stereotype, and not as a person that has a “unique constellation of characteristics”, and we tend to add the person to an already known category. Nielsen (2004) argues that the more material is presented to us, the less we need to draw on our previous experiences and encounters.

The effects of the stereotyping in (virtual) teams is two-folded. On the one hand, our expectations derived from our stereotyping end up becoming “self-fulfilling prophecies” explained via the well-known Pygmalion effect (Livingston, 2003). On the other hand, it can have an impact on our team members’ trust amongst each other. However, both factors have an impact on the team’s productivity.

Pygmalion effect and stereotyping

The Pygmalion effect has been widely researched by behavioral scientists, especially in school settings, and it is explained by Livingston, who coined the term Pygmalion, as: “The lucky child who strikes a teacher as bright also picks up on that expectation and will rise to fulfill it. This finding has been confirmed so many times, and in such varied settings, that it’s no longer even debated.” (2003)

The Pygmalion effect is valid in organizational settings as well: an experiment from 1961 on teams in organizational setting, explained in detail in this article in Harvard Business Review, concluded that the productivity of the team that was expected to perform well improved dramatically, while the productivity of the team who was considered as not having a chance to meet the quota, decreased dramatically. (Livingston, 2003)

The beliefs we have of others (either true or expected due to our stereotyping), will influence our communication with them. Livingston (2003) describes how managers are more effective in communicating their low expectations than they are at communicating their high expectations, even though we might believe differently. Passive behavior, indifference, and low frequency of communication could all be perceived as signs of the low expectations we have as leaders from our employees.

The risk we are running is having low expectations of certain groups of people due to stereotyping, and them lowering their performance to meet our expectations.

Trust and stereotyping

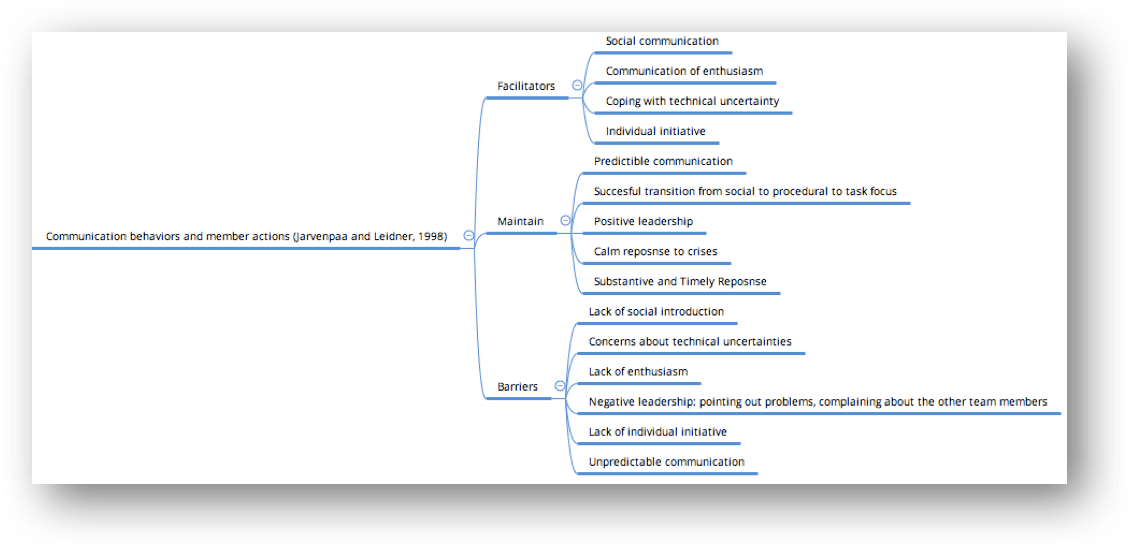

As discussed in a previous blog post, an important step in building trust is calculated trust, and a step in building calculated trust is the social introduction. Trust in virtual teams (and any types of teams) is important as from it derives the team’s motivation, which impacts team’s performance. (Zacarro and Bader, 2002)

Jarvenpaa and Leidner (1998) have discovered that a commonality amongst teams that start with low trust levels, is the lack of social introduction. We could conclude from here, that a poor or absent introduction of the team members could lead to stereotyping and low levels of trust.

Virtual teams and stereotyping

Stereotyping is true for teams that work together, but my hypothesis is that it is even more poignant in virtual teams. As layers of virtuality are added, we have less information about the persons we are interacting with: for example, we are not able to see their facial expressions or body language, which is crucial in interpreting sarcasm, humor, or irony. Research shows that: “In the absence of individuating cues about others, we build stereotypical impressions based on limited information.” (Lea and Spears 1992).

This made me wonder which “unique constellation of characteristics” do digital leaders need to encourage virtual team members to disclose about themselves in order to decrease the level of stereotyping and hence, increase the level of trust in virtual teams? Parallel, which information do leaders need to know about their employees in order to increase their expectations of their employees?

Engaging Persona

In I4L we have the honor to have Lene Nielsen as one of our team members – Lene has researched personas for over 15 years. When I told Lene what is my preoccupation in regards to stereotypes, she introduced me to the concepts of “rounded character” from filmography, and the concept of engaging personas.

In her Ph.D. (Nielsen, 2004), Lene has developed a model for engaging personas, based on various rounded character descriptions. The engaging personas model, inspired from rounded characters in filmography, was developed with the purpose of helping companies and designers understand their target audience better. The mechanism behind is to avoid “schematas”, which is the tendency to fill in the missing information with pre-learned models of the world – in other words, stereotyping.

I propose engaging personas as a model for digital leaders to introduce themselves and team members to each other.

According to Nielsen (2004), the characteristics of engaging personas, are:

- Body: “bodily expression and a posture, a gender and an age” (p. 155).

- Psyche: “the present state of mind, persistent self-perception, character traits, temper, abilities and attitudes” (p.155);

- Background: “present knowledge, job and family relations, and persistent beliefs, education, and internalized values and norms” (p.156);

- Emotions: “emotions, intentions, and attitudes including ambitions and frustrations, wishes and dreams” (p. 156);

- Cacophony: “character traits in opposition as well as peculiarities” (p.156).

The “engaging persona” characteristics can be used by leaders as a framework for the type of questions they could ask employees to present themselves, but also as a guidance for leaders on how to introduce themselves to the team and act as a role model, which is a critical behaviour for effective team leadership, according to Wade, Mention, and Jolly (1996).

The above framework can be used in the first (virtual) team meeting, or for introducing a new team member – be it a virtual conference call, audio or video, or a message that is written on the enterprise social media or online community wall.

The “Body” characteristic can be compensated for in a virtual setting with a profile picture and a requirement for every new team member to have a profile picture – paralleled, if possible, with a video or audio conference, where team members can be introduced to multiple physical dimensions of each other: seeing, hearing, reading facial expressions, vocal inflections, verbal cues, gestures and body language. These communication dynamics are one of the challenges that virtual teams face, according to Kayworth and Leidner (2015), and in many instances, our profile pictures are the only physical dimension we can convey about ourselves in virtual settings.

“Psyche” can be conveyed through discussing someone’s relation to the technology used in a project for example, or their beliefs and use of technology. For example, I could say about myself that I do use social media, although I have privacy concerns and have a deep belief that social media can be a waste of time and cause dependencies. This shows contradiction and the lack of settlement in my view of social media, as well as openness and skepticism simultaneously towards it.

The “Background” dimension is important for leaders to emphasize on when introducing new team members to each other, pointing out special abilities, courses, experiences or success that team members have achieved previously, and therefore setting the stage for having high expectations of them and of each other. As seen previously, our expectations of each other and of our employees have a direct influence on the team’s productivity. As Livingston (2003) formulates it: “How can you get the best out of our employees? Expect the best.”

Kayworth and Leidner (2015) point out that one’s background might be distorted by the high levels of anonymity that virtual settings allow for, as we can change our username or not fill in information about our job title, location or even choose to set ourselves as “invisible” to the team if we wish to. It is important for digital leaders to set the stage of how employees should fill in the information required in their online profiles used for collaboration, as well as establish standards for collaboration.

“Emotions” can be conveyed by expressing what we feel in relation to the task, project, colleagues or by how we talk about the same. If I say: “I am really excited to start working on the project” – I will convey a high energy and enthusiasm. Similarly, if I say: “Let’s hope we manage to pull the deadline”, I might unwillingly convey skepticism towards my team’s capability to meet deadlines, as well as apathy.

“Cacophony” is described in a guideline for writers by Rukov (2003) as 1+1+1, where 1+1 refer to two oppositional character traits, while the last 1 is a peculiarity. For example, I could say about myself that I consider the cake that we bring to our workplace as a replacement of the social cigarette of the past decade, but I will still accept an invitation to eat cake with my colleagues – this would represent the two oppositional character traits. A peculiarity is that I own 25 plants and counting.

In summary, stereotyping can lead to low levels of trust in virtual teams, as well as set the stage for expectations lower than our employees could raise up to, which will impact a team’s productivity levels. A way to combat stereotyping is making sure to introduce ourselves and our team member’s to each other in a way that doesn’t leave space for stereotyping. A way to do so, is borrowing the framework of building rounded characters from filmography, which can help us build engaging personas around ourselves and virtual team members and use collaborative software to its full potential to create our online profile.

Bibliography

- Cardwell, M. (1996). Dictionary of Psychology. Chicago IL: Fitzroy Dearborn.

- McLeod, S. A. (2015). Stereotypes. Retrieved from simplypsychology.org/katz-braly.html

- Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Leidner, D. E. (1999). Communication and Trust in Global Virtual Teams. Organization Science,10(6), 791-815. doi:10.1287/orsc.10.6.791

- Lea, M., & Spears, R. (1992). Paralanguage and social perception in computer-mediated communication. Journal of Organizational Computing, 2, 321-342.

- Timothy R. Kayworth, Dorothy E. Leidner (2002) Leadership Effectiveness in Global Virtual Teams, Journal of Management Information Systems, 18:3, 7-40, DOI: 10.1080/07421222.2002.11045697

- Livingston, S. (January, 2003). Pygmalion in Management. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved July 4, 2017, from https://hbr.org/2003/01/pygmalion-in-management

- Macrae, C. N. and Bodenhausen, G. V. (2001), Social cognition: Categorical person perception. British Journal of Psychology, 92: 239–255. doi:10.1348/000712601162059

- Nielsen, L. (2004). Engaging Personas and Narrative Scenarios(Doctoral dissertation, Copenhagen Business School).

- Rukov, M. (2003). “Persona workshop”. L. Nielsen. Copenhagen. Sigchi.dk

- Wade, D.; Mention, C.; and Jolly, J. Teams: Who Needs Them and Why? Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing, 1996

- Zaccaro, S. J., & Bader, P. (2003). E-Leadership and the Challenges of Leading E-Teams:. Organizational Dynamics, 31(4), 377-387. doi:10.1016/s0090-2616(02)00129-8