This article is for digital leaders that want to understand how to build trust in virtual teams.

Research shows that trust is a very important factor in virtual teams’ motivation. It can be defined as “the beliefs and expectations that members have of each other, that each member will live up to agreed-upon commitments, that each member is acting with good intentions on behalf of the group, and that each will work hard on behalf of the group.” (Zacarro and Bader, 2002)

Early research on trust and virtual teams suggested that trust is difficult to obtain in virtual teams due to that “trust needs touch” and face to face interactions. (Handy, 1995)

Berne (2015), the father of Transactional Analysis – discusses that the fundamental unit of social action is a “stroke” – which denotes an act of recognizing another’s presence.

If Anna says “Hello” and Claus replies with a “Hi!” they have exchanged two strokes. If Anna asks a question – hence one stroke – and Claus does not answer she will be puzzled. How many times will you say “Hello!” to someone who doesn’t respond? And how likely is it, in such a case, that you will not trust a person who did not repay a stroke when they later want to build a relation to you? You may rather want an explanation for their earlier behavior. Or, in Transactional Analysis vocabulary: you want your strokes back and possibly a few extra strokes to regain your trust.

It is important to note that exchanging strokes does not imply only verbal exchanges, it can also mean meeting expectations, keeping your word, smiling or waving back to someone, answering an email, liking someone’s update, giving feedback to employees coming forward with initiatives and ideas, compensate extra hours – anything through which you are “acknowledging someone’s presence”.

Relations, according to Berne, are built upon exchanges of strokes. In the context of psychological contracts “an individual’s belief about the terms and conditions of a reciprocal exchange agreement between the person and another party” (Robinson 1996). When we enter a work collaboration, we expect a set of conditions under which we will exchange our “strokes”, and our trust depends on whether our expectations are met or not.

Zacarro and Bader (2002) propose a three-stage framework for understanding and building trust in virtual teams:

- Calculated trust: when although we have no proof, we decide to trust the parties we collaborate with;

- Knowledge trust: emerges when team members have interacted for a while and know what to expect from one another;

- Identification trust: “emerges when team members come to agree on how the team as a whole should respond to challenges in their external environment through continued dialogue with each other.” The team is an entity they can identify with, and each can act as a representative of it when appropriate.

Digital leaders play a vital role in helping their (virtual) team’s trust move from calculated trust to the highest level of trust, which is identification based.

Now, I would like to step back from all the theory and invite you to dance. In order for us to dance, we would need a dancing floor, shoes, music, a dancing style, but what’s most important, we need a leader in our dance, otherwise, we would end up stepping on each other’s toes. I might be a good dancer, or I might be a bad one – at this point, you don’t know and, since you have accepted my invitation, your only chance is hoping for the best.

Similarly, when a new team is formed, the leader needs to define the roles that each team member will play, describe the tasks, introduce the team members to each other and to the technology they will be using, and assert the expectations. This newly formed space, which is explicitly introduced, is the basis for building calculated trust.

Next, I will explain the steps of the dance and the rules. I will guide and motivate you: if you make a correct step, I will encourage you to make more of those steps, and if you don’t, I will make sure to re-adapt my instructions to your understanding. At this stage, I will know which steps you are good at, and for which steps you need more practice, and I will also know how you react to success and failure – and so will the ones watching. This is knowledge-based trust, and as a digital leader, it is important to provide prompt feedback, establish standard operating procedures, make sure that the tasks are clear to each individual, and react fast (and in calm and positive manner) to when things don’t go in the desired direction.

When you are ready to take over and you know the steps well and you are confident, you can lead the dance and we can sign up for a dancing competition. At this stage, digital leaders have established a high trust team, where members can take the lead and responsibility for various tasks. It is important to maintain a spirit of common purpose and encourage team members to extend their exchanges to more socially-oriented and personalized exchanges.

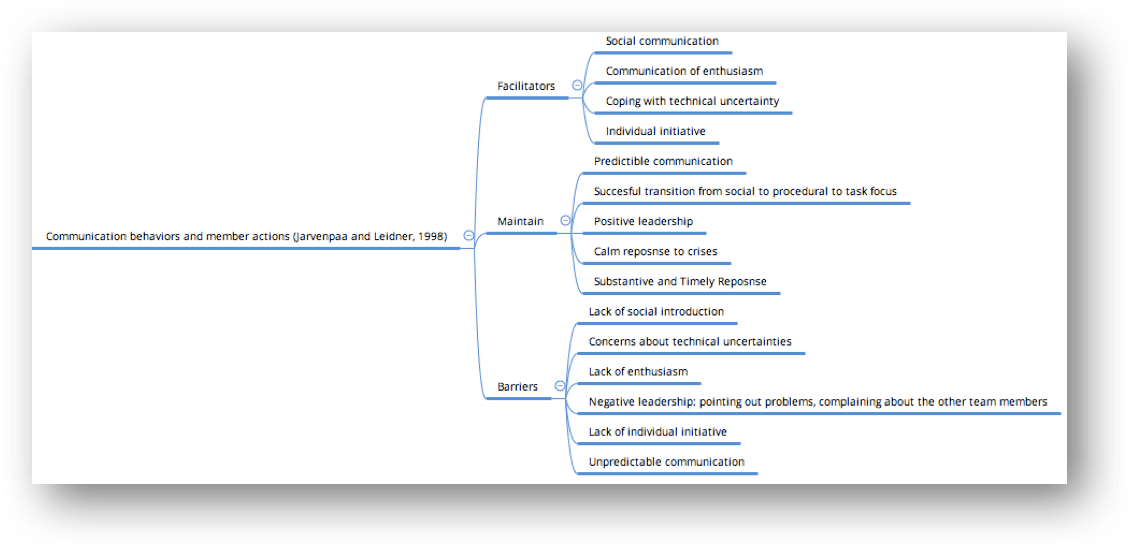

Jarvenpaa and Leidner (1998) support the dance metaphor, as it can be seen in the figure below, emerged from their analysis on which behaviours facilitate and maintain trust in virtual teams, and which behaviours represent barriers, based on 12 virtual teams:

According to them, timely response is also important, as well as predictable communication, calm response to crises and positive leadership. Unpredictable communication, concerns about technical uncertainties, negative leadership and lack of enthusiasm have all been proved to represent barriers in building trust.

I’ve chosen the metaphor of a dance because it depicts best how the exchange of strokes should happen between a leader and team members: consistently and timely. In a dance, you can’t ignore a wrong step – it will affect the dance, while one good step after another will lead to a smooth dance. Similarly, if you react negatively to a wrong step, you will affect the mood of the dancer and chances are, they won’t want to dance with us again. It’s a good way to think of how to interact with our employees: timely, consistent, and positive, like in a dance.

Thank you for the dance!

In I4L, we don’t dance, but we disseminate research for practitioners and because we want to make research as memorable and entertaining as possible, sometimes we story tell. Make sure to subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on Twitter @i4l_dk.

Bibliography

- Berne, E. (2015). Transactional analysis in psychotherapy: a systematic individual and social psychiatry. Mansfield Centre, CT: Martino Publishing.

- Handy, C. (1995). Trust and the virtual organization. Harvard Business Review, 73(3), 40–50.

- Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Leidner, D. E. (1999). Communication and Trust in Global Virtual Teams. Organization Science,10(6), 791-815. doi:10.1287/orsc.10.6.791

- Robinson, S. L. (1996). Trust and Breach of the Psychological Contract. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(4), 574. doi:10.2307/2393868

- Zaccaro, S. J., & Bader, P. (2003). E-Leadership and the Challenges of Leading E-Teams:. Organizational Dynamics, 31(4), 377-387. doi:10.1016/s0090-2616(02)00129-8